Thinking borders, oceanically.

On The Past is a Foreign Country by Michikazu Matsune and Jun Yang

Some twenty years ago, the artists Michikazu Matsune and Jun Yang met through mutual friends in Vienna. “Becoming friends”, they tell me in a conversation, means “being yourself”. This ‘intimacy of friendship’, as Derrida writes, lies in the sensation of recognising oneself in the eyes of another. For Michikazu Matsune and Jun Yang, their most obvious commonalities are their sense of humour, as well as their transnational and inter-related living and working processes. Born in the port-city of Kobe in Japan, Matsune lives and works in Vienna since the 1990s as a performance artist and educator. For his stage-performances he often engages with historical anecdotes in his personal artistic style, as a method to examine cultural ascriptions and patterns of social identification. Yang was born in Qingtian in China, from where his family emigrated to Austria when he was four years old. His artistic practice that encompasses various mediums, including film, installation and performance, develops through continuously shifting cultural contexts, as Yang is based in three cities, Vienna, Taipei and Yokohama. While there are many artists that try to, fashionably, list multiple geographies to their practice, there are certainly not many who manage a transcontinental engagement with as much endurance as Jun Yang.

In their respective bodies of work, Matsune and Yang often engage with the conceptual fluidity of identity. Over the years of their friendship, their exchanges have reflected in each others pieces. In his 2015 performance Dance, if you want to enter my country!, Matsune investigated the profiling and surveillance mechanisms that apply to international travellers. For this purpose, he manipulated his biometric passport portrait by shaving off his eyebrows and glueing them onto his skin as a moustache. While Jun Yang contributed to the textual script for this performance, Matsune’s photo, in return, featured in Yang’s 2019 project The Artist, the Work and the Exhibition at the Kunsthaus Graz. The Past is A Foreign Country would, still, be the first time for both artists to conceptualise and perform an entire piece together, promoting them to thematise the risk of two friends putting themselves through the ‘lockdown’ of a shared creation process, and having to bear the responsibilities of such endeavour. Premiered at the 2018 Gwangju Biennale and later shown in Vienna and Taipei, it demonstrates for a collaboration in which both artists’ individual practices converge, as they engage the semantics of mobility to articulate a relational poetics. The adaption for Taipei Arts Festival had to especially find ways to respond to the circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic, as travel restrictions made it impossible for the performers to both be in Taiwan physically. It therefor comprises of two parts: a 45-min screening of the live-work, that is followed by a specially created annex, Dear Friend.

“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there,” wrote L.P. Hartley in his 1953 novel The Go-Between. While the phrase may be well-known and audiences may even “come back loud and strong on their own with the second half”, very little people may actually be able to recall the book’s narrative, or even know the literary source. Their choice of title thus somewhat presupposes how Jun Yang and Michikazu Matsune understand the performance setting – as a horizontal assemblage of rhizomatic narratives, which engage historical and intercultural frameworks to elicit new connections. Seemingly comparing their own to other collaborative missions, they recall historic duet constellations, such as Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay climbing Mt. Everest, as well as Neil Armstrong’s and Buzz Aldrin’s arrival on the moon. The latter links in to the contemporary pandemic situation in a comical manner, since the crew of the spaceship, upon returning to earth had to quarantine in a metal tin for three weeks, to prevent the spread of any ‘alien contamination’.

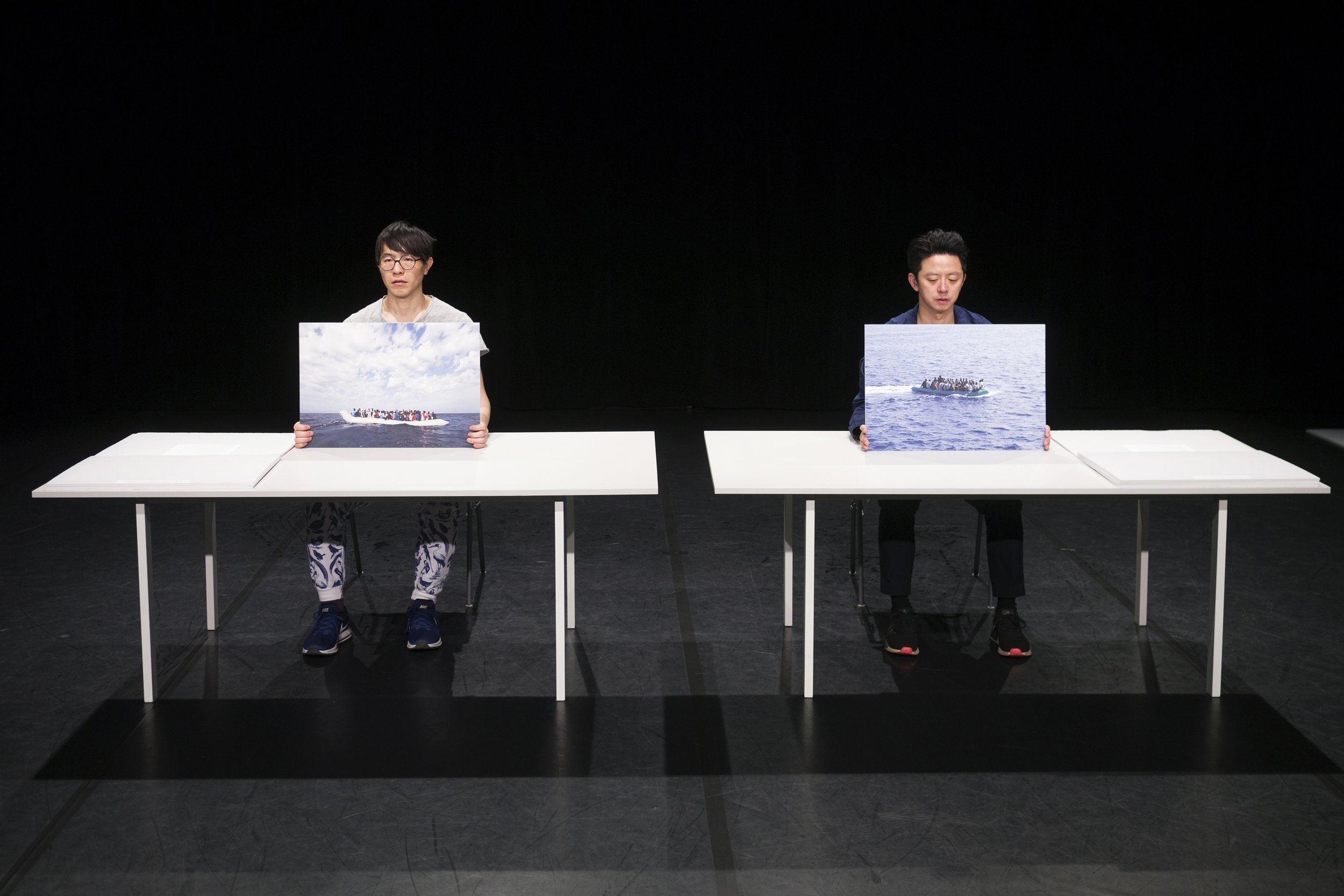

The performance employs a mode of pictorial storytelling inspired by Kamishibai, a form of street theatre and storytelling from Japan. This oral storytelling form first emerged as street-performance in the 18th century and would later develop in diverse ways in the country’s different regions. For the Japanese context, Kamishibai is said to have been widely enjoyed during the Great depression of the 1930s and in the post-war period, until the advent of television during the mid-20th century. Kamishibai were performed by a narrator who travelled with sets of illustrated boards, which were then placed in a miniature stage-like device. Stories, sometimes unscripted, were told alongside the changing of images and accompanied by sounds that the artists made. Some outgrowths of the form would, for example, feature a stage to enhance the performer’s presence; while other forms would use the stage to have the storytellers “retreat behind” it. The art of the latter would be considered in creating “an effective oral ‘soundtrack’ to enhance the pictures without drawing undue attention to the performer.” As a performative past of Japan, one of the places that link together Matsune’s and Yang’s biographies, Kamishibai methodically informed the staging. The performance narrative is accompanied, guided, and sometimes also interrupted by photographic image boards. Performing alongside these images, in some moments the artists recall Kamishibai’s potential of hiding, gesturally concealing their identity with the photographs. Yet, in most parts, they present their narratives in a frontal, reportage-like manner, facing the audience. The photo-form then functions both as dramaturgic guidance and itinerant interruption. It holds the space to speak through images, show up through images, and even provides for images to communicate with each other, to approach each other.

border lands

The staged collaboration radiates from the artists’ East Asian backgrounds, and how, consequently, Matsune’s and Yang’s life-dynamics have been shaped by factors of interculturality and mobility. Their inter-Asian essay looks at and challenges the narrative framing of the region and its transnational, global relations. Most of the narrative fragments presented concern the experience of borders, both metaphorically and literally. As an ambiguous concept, the border holds space for positive and negative attributes, inclusion and exclusion, allowing for processes of identification, as much as for processes of distancing. Matsune’s and Yang’s presentation is involved in this complexity, as it includes reflections on borders as regions, everyday rituals as well as political events performed at borders; stories of individuals testing on their limits and humanity trying to overcome its planetary ‘embordedment’. Instead of regarding a border as a dividing line that separates two entities, whether they are state leaders, civilians or territories, their outlook focuses the performative foundation of borders, what can be called their “mediating moment”.

Among the historic junctions mentioned in the performance are the entering of the US Black Fleet into the harbour of Yokohama in 1853, which led to the re-opening of Japan, and its subsequent rise as a regional imperialist power. The narration further approaches the flag ceremony at India’s and Pakistan’s Wagah border, as a daily evening ritual “at the gates, which for a long time were the only way between areas that were once united as one country, and that are now two”, as Matsune recalls. Attempting to unravel the inherent performativity of state-official ‘border practices’, another narrative pitstop is made to review the historic April 2018 inter-Korean summit meeting between South Korean president Moon Jae-in and Supreme Leader of North Korea, Kim Jong-un. The occasion of this summit, focused on the denuclearisation of the peninsula, was the first time since the end of the Korean War in 1953 that a North Korean leader entered the South's territory. The meeting started with the two politicians shaking hands over the demarcation line. Moon then accepted an invitation from Kim to briefly step over to the North's side of the line. With many elements expressly designed for symbolism, the event’s affective frontiers provide Jun Yang’s and Michikazu Matsune’s exploratory curiosity with fertile ground.

Revisiting this gestural climax of recent political history, Yang observes that “photographers both from the side of the North and that of the South are running in and out of each other’s frames, as to not be included in the photographs of each other.” He points to how, while bolstering transnational aspirations, the scenic mediation of international politics reveals political history as a series of constellations performed by (often) two men. Ultimately geared to investigate the arts’ role in what are considered ‘historical settings’, Matsune’s and Yang’s essayism arrives at how, inside the Inter-Korean Peace House, carefully selected paintings and photographs were displayed to impress the Northern visitor. In the banquet hall, a painting by artist Shin Tae-soo depicted Baengnyeongdo, an island that, due to its geographic position has, as a ‘contact zone’, seen several naval skirmishes between the two countries. Thinking of borders with islands, and of islands with borders ultimately expands the imagined straightness, to involve the element of water, tides, flows, and foam. With Baengnyeongdo, and also Taiwan serving as examples, islands thus form particular kinds of border areas, such that “point to flows of people, movements among islands, the relations between water and land and between [other] islands and the mainland[s].”

oceanic borders

In the very beginning of the performance, Matsune recalls how the ocean had been an important presence in his childhood in Japan. The photo alongside which he speaks, shows him with his siblings, growing into life together, in close proximity to the sea. He describes their shared sense of the world as shaped by interactions with the water and by learning how to swim. His story, also in a larger sense, prompts an invitation to think oceanically, to anchor one’s understanding of existence not in an economic, nation- and land-based sense, but rather in a metaphoric sense of shared regional (and global) planetarian identity. As the Fijian-Samoan scholar Epeli Hauofa, who was the first to draw a manifest of oceanic thinking suggests, the ocean “it is our most wonderful metaphor for just about anything […]. Contemplation of its vastness and majesty, its allurement and fickleness, its regularities and unpredictability, its shoals and depths, and its isolating and linking role in our histories, excites the imagination and kindles a sense of wonder, curiosity, and hope that could set us on journeys to explore new regions of creative enterprise that we have not dreamt of before.” As a manner of “making apprehensible modes of historical and geographical consciousness that exist not behind or instead of modernity’s, but rather beside them, complexly interwoven with them” oceanic thinking, in its full utopian dimension, binds Matsune’s and Yang’s performance narrative. It characterises connections that are in constant motion, impacted by migration and travel.

Understanding events from an oceanic perspectives requires to rethink country-based spatial and temporal logics. Matsune therefor dives into the writings of Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, who in Mare Liberum (1609) argued that the sea was free to all, and that nobody had the right to deny others access to it. Historically however, Japan proves as a specifically antithetical case, as in the country entered into a self isolation period of more than two centuries, which only ended with Commodore Perry’s arrival in the port of Yokohama in 1853. Jun Yang, later in the performance, describes himself in exactly this city, as he recalls a visit to the Yokohama Immigration Bureau office. “I try to picture the US Black Fleet, the gunpowder ships entering the harbour.” To extend his resident status in Japan, he is asked to fill in a form, point 17 of which, titled “reasons / family”, allows the following options: Biological child of a Japanese national or Child adopted by a Japanese national. The process thus foresees that only a child of a Japanese national would be eligible for residency. The nation-state ideal that manifested in the modern era has entrenched politically constructed borders, defining national identities as key and uniform, which in turn leads to an exclusion of undesirable non-nationals as threats to an imagined national homogeneity. Confronted with the form’s binary preselection which eliminates other potential realities simply by excluding them, Yang suggestively muses to “apply the other way around”, in his case meaning “not as a child of a Japanese national, but as the biological father to his two Japanese children.” He claims his role as a father within the embodied dimension, as a regular visitor – who, for this purpose needs to extend his residency status. His story yet demonstrates, how transnational biographies are often haunted by an intimacy of the factual, as the individual becomes attached to the bureaucratic. Introducing to the audience his approach, to legally ‘become part’, as one that favours interdependent connections instead of an ethics of simple and reductive dichotomies, he addresses an ethics of care beyond the subjective, embedding the personal within the political. Such perspective emphasises that “the cultural construction of citizenship does not take place only within the confines of the policy sphere, but it is also shaped by the continuous re-elaboration of discourse in the public sphere.” Lived relationships, rather than static dispositions then constitute the frameworks of belonging, to a cultural setting and its affective knowledges.

living and thinking (with) borders

Transborder movement and the subsequent experience of border-selves and their inherent multiplicities have, for both Jun Yang and Michikazu Matsune, been conditional to building and sustaining their lives and artistic careers. The conjuncture of art and migration can

potentially be explored in myriad ways, as artists are often viewed to challenge frontiers and create spaces of in-betweenness and encounter that challenge hegemonic fixities. In this context, twenty-first century postcolonial East Asia may be regarded as a paradigmatic site to challenge the art world’s only seemingly inclusive dispositive. Jun Yang’s sharing about the realities of the migratory experience, however, forces us to rethink the naive and bleeding-heart opportunism that largely dominates circulation narratives of the visual art as well as performing arts markets. Within the context of his work, unafraid of challenging institutional forces, he keeps returning to the crucial discussion for what and for whom art works. The Past is a Foreign Country essentially presents a narrative that expands the view of the gifted, visionary, internationally working artist; to include personal relations and the multifaceted responsibilities which they entail. Relocating, in this case, is less connected to a quest for becoming visible, but expresses a need for becoming present and co-present. Moreover, as the performance toured during the pandemic, The Past is a Foreign Country reflects how circumstances of Covid-19 magnified the challenges faced by anyone who had been used to realise their presence transnationally. People living and working between different geographies, in an interconnected world, were suddenly left with opaque hopes over when and how it would be possible to travel again. With the discourse of borders strongly linking to the exclusion of all that is foreign, hybrid forms of living became seen as threats to the carefully mediated construction of sociopolitical ‘immunity’. This becomes especially evident as the Taipei performance is followed by the additionally created work Dear Friend. Yang performs live on stage and is joined online by Matsune from Vienna. They read out letters to one another, addressing their felt sense of loss of not being able to meet. Matsune, who as a consequence of disease-prevention policies had been unable to travel to Taiwan, becomes present only through his voice, describing his experience of the pandemic in Central Europe.

Both the lecture and letter forms that the artists chose for their performance make processes of knowledge formation (and transformation) visible and understood. Allowing for such constellations, Matsune’s and Yang’s essayism harnesses concepts of interculturalism, geo-spatiality and separation, in interpersonal and playful scenarios. The performance, in this sense also documents how Yang’s and Matsune’s biographies and life-itineraries have shaped distinct geographies of knowledge, to which the collaborative working dialogue serves as a sort of hermeneutic tool. While, certainly, the intention in this case, is not to impose a fictive sense of togetherness, as ‘kinship’, the content they decide to share rather turns to an understanding of and, perhaps, even commitment to ‘Asianness’ as a geopolitical responsibility. As Rossella Ferrari writes, it is “not just Western epistemological and economic privilege that demands scrutiny, but also the political economies and financial mechanisms whereby inter-Asian hierarchies of empire and capitalistic domination can become manifest.” In this regard, The Past is a Foreign Country and Dear Friend engage with the quest of decentralising and dislocating Western, as well as Inner-Asian colonialist pasts.

I would like to end this essay on a personal note. Although we have a common connection through living, at least part-time in Vienna, I first met Jun Yang and Michikatsu Matsune in Yokohama. It was at the occasion of TPAM Performing Arts Meeting in February 2020 that we started engaging in conversation. Over many evenings, I have been lucky to continue this exchange with Jun Yang in Taiwan, from where I returned back to Austria later that year. I am thus especially grateful for having been asked to write about Jun Yang’s and Michikatsu Matsune’s work, to keep our conversation going and growing. Thank you for sharing your time and views on this interconnected world, dear friends.