The Dialectics of TING 聽的辯證法

Catalogue essay for Ting-Jung Chen, published by TFAM Taipei Fine Arts Museum. 2022

Ting-Jung Chen is an attentive observer and listener, whose practice resembles that of a cultural archivist, an “assemblage-maker.” Titling her first solo show in Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), “This Is A Complex Sentence. 十六分之一休止符後”, the artist proceeds to approach the world as if it were language. Under this unit of grammar, she presents a total of ten works, which are spatial configurations, relations of frequencies and explorations of art institution vectors. Chen forms constellations, “unmuting” the silence of the objects and documents she engages with and brings them to speech. As the title also suggests, the presentation utilizes a specific kind of arrangement, whereby its parts are organized not into just any kind of sentence, but into a complex sentence. It highlights how language not only serves as a tool of curious exploration, but as an intellectual power, a capability to access and organize information. As an artist who divides her time between East Asia and Central Europe, Chen’s works and their arrangements in the cross-shaped gallery space reflect on the capacity of being multilingual and plurivocal, both in a literal and metaphorical sense. They correspond to Chen’s observations, shaping a critical poetic space that engages different aspects of instrumentalism, identity, iconicity and conflict. While this exhibition offers a myriad of potential access points for critical discussion, my essay chooses to approach it from the dimension of movement, focusing on its combination of spatial and temporal elements and how these engage visitors in an immersive setting. This text will recurrently touch upon the concept of assemblage to trace the artist's logic and methodology in her positioning of a “complex sentence.”[i] Assemblages highlight not only the contextual and performative aspects of the elements they contain, but also their (political) agencies.

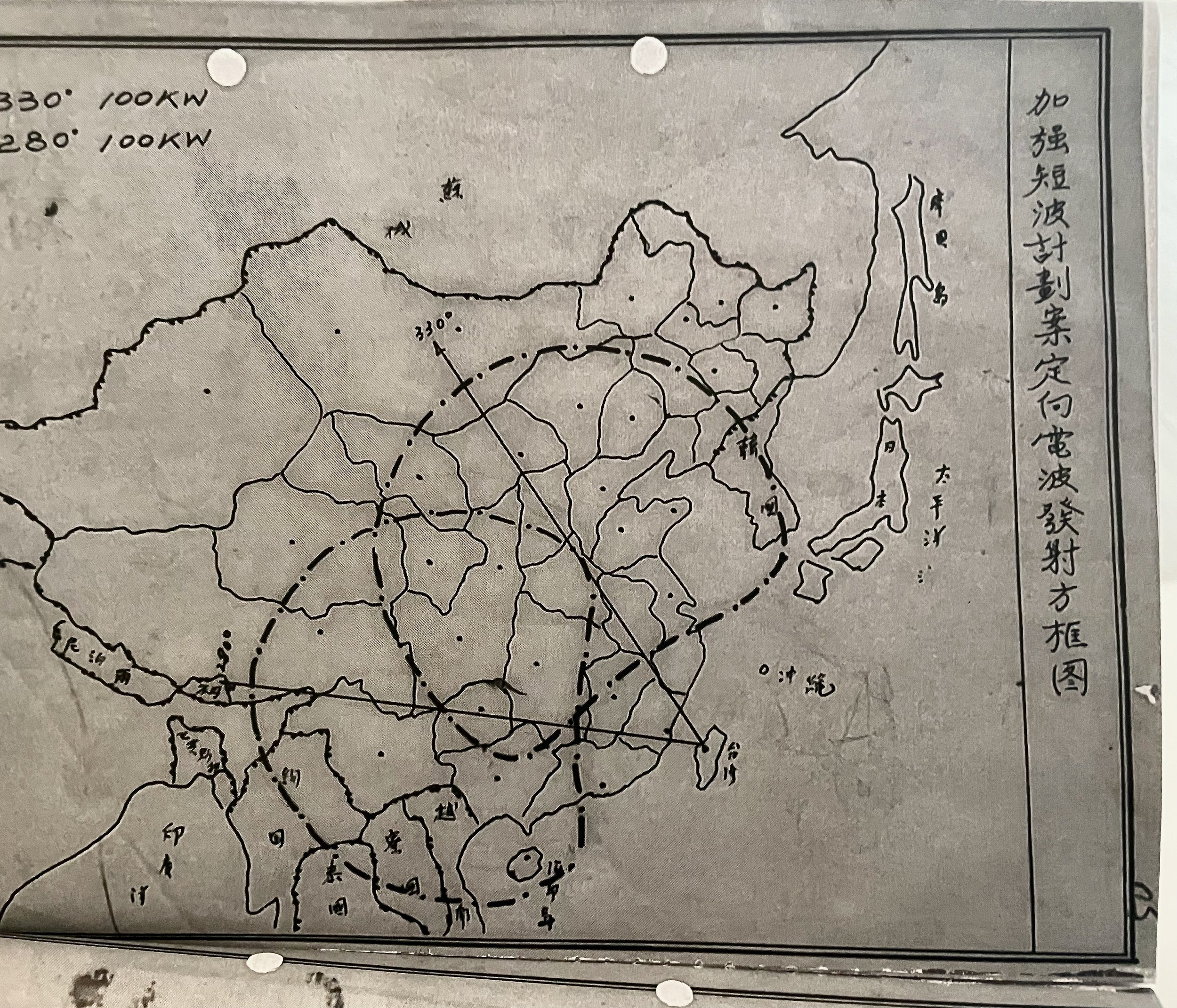

In “This Is A Complex Sentence.", visitors first enter a space of abrupt darkness, before traversing into the natural light of the rooms at the further end of the exhibition. Upon entering, each person must write their name on a card, which they trade as their “token” to receive a pair of headphones that mediates the exhibition as an immersive acoustic zone. A six-channel sound installation guides the visitors into its strangely overlapping and mysteriously invisible spatial logic. The central work of this solo show, Vanishing Point 消失點 (2022), features love songs that the artist recomposed, mashing together both patriotic and banned songs from the 1930s-70s in Taiwan, as well as lovesongs that were used as “sonic weapons” in Taiwan’s radio broadcasts to China. Written by male songwriters and performed by female singers in Chinese, the songs were given romantic titles, such as My Love Goodbye 情人再見, Moonlight Serenade 月光小夜曲, or Wish You Come Back Soon 望你早歸, to evoke nostalgic feelings from soldiers. About thirty different female voices can be encountered altogether, merging with frequencies of sine waves and bells that ring from time to time. The artist has installed a “broadcasting system” across three rooms of the exhibition, using small circuits to frame the audible range of the different sound pieces. The listening experience thus depends on each person’s viewing pace, exposing visitors to different “acoustic territories”. The invisible architectures of sound signals and their transmission shape unique contours around the bodily presence of the audience. When listening to the voices and sounds via headphones, visitors may be lulled into feeling that they recognize particular fragments. The seemingly familiar, however, is in fact a result of a complex, historical trajectory of essentialism, through the instrumentalization of feminine voices for propagandistic purposes. A deeply unsettling sentiment accompanies the homogeneity of the lyrics and the stereotyping of female roles inscribed therein.

Glass glitches

On the visual level, long, horizontal light strips and a gap cut out of the wall serve as the dominant spatial coordinates for the exhibition's initial passageway. The following spaces then organize the perception along vertical axes instead, presenting black metal poles with glass sculptures that stretch from floor to ceiling. This installation, called Speaking Length 發音弦長, assembles a total of twelve mouth-blown glass objects. Their arrangement choreographs the expanse of the rooms. Proposing curious inquiries in service of remapping physical space, the glass works are placed at different levels of height. Capturing the light, their diaphanously veiled and shaded coloring gives illusionary qualities of depth. In their stillness they express a state of universal motion: they dwell in movement. The glass sculptures defy formalism also in their explorations of the material’s limitations and potentials. In the world of glass production, Chen’s sculptures in fact embody error, but she exploits their bulging shapes and twisted folds to create fluencies that challenge the limits of what glass can do. As material glitches, they highlight vulnerability, by entering a radical exploration of the spatial form – the spaces they contain create an interplay that provides traction for thinking about im/materiality.

For their production, the artist worked with a local glass-manufacturing company in Lukang, in Taiwan’s Changhua County. Every step of the process had to be tightly controlled in order to avoid internal stresses that put the glass at risk of breaking apart. There is unpredictability in such a process, even when working with skilled craftsmen and versatile machinery. The resulting, fragile objects can be characterized as resilient, almost stubborn. With their internal veiling, layering, and patching together of multiple parts, they perform “resonating” glass bodies (Chen). Their communal texture encapsulates aerial thresholds, as gatherings of matter and chromatic energy. The shapes of some resemble that of the torso, others look a bit like human ears or even have forms similar to the body’s inner organs. Their positioning in the setting further suggests their function as speakers, while in fact they are neither the source, nor the transmitters of sound. Still, they point to an agency of (and through) the invisible, merging the in- and the outward, and thereby materializing thoughts and concepts that are to reappear throughout the exhibition. In this aspect, they communicate with the other, frequency-based works: as part of the electromagnetic spectrum invisible to us, radio waves, just as those in a Bluetooth network, resist our immediate eyesight. Chen directs our awareness to the material forms we see and hear through, to in-between spaces and the infrastructures that allow for “exchange over space.”[ii]

Curtain calling

The gallery’s northern windows are guarded by a floor-length curtain, fragmenting the view to the outside. Every nine minutes, a very low-frequency sound lifts its fabric with disturbing strength. Two subwoofers blast out the roaring noise that almost makes the gallery walls shake. Recalling a dualistic condition, this work is called Twins 雙生(2019/2021). Its untamed force seems to come in from the museum’s outside, as if an air strike were brushing across Taiwan’s hills from elsewhere. With each such iteration, Foucault’s Pendulum 傅柯擺 (2022) that is installed next to the curtain, is triggered to swing for yet another round. This irregularly-shaped miniature cites a physical model that demonstrates the Earth’s planetary rotation. Yet here, its action is completely out of balance. Triggered into exhaustive movement, it hits against the wall with the sound of a bell’s sharp overtone, slowly and gradually scraping the paint and paneling. The pendulum’s bronze weight has been cast from a stone that the artist collected on the Kinmen islands during her research on the memories of Cold War acoustic warfare between Taiwan and China. Here in the gallery, Chen has placed a bench for visitors to sit and observe the theatrically-constructed scene, and once the Twins’ low tones subside, a woman can be heard singing Moonlight Serenade, the Mandarin adaption of an originally Japanese propaganda song[iii], in a thin voice. Three small books are laid out here as well, to provide interested audiences with historical background on radio programs and their formatting for the purpose of sonic warfare between Taiwan and China.

Unwhitening the cube

One key feature of this exhibition is its suggestion to associate the installed works with the material geographies of the museum’s surroundings. Since the globalized art world has embraced Western modernism’s transposition of perception, a gallery space usually follows an almost sacramental inwardness in its formal presentation: the walls are painted white, the floor is polished, and ceiling lighting becomes the primary, and often only, source of light. The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. As Taiwan’s first museum for “contemporary art”, TFAM has adopted this model of the unshadowed, white and immaculate exhibition space, and consequently, the cross-shaped presentation area of Chen’s solo show had not seen daylight in over a decade. Chen however decided to open the white cube to include views of the city and its infrastructure into the concept of the exhibition, proposing a conscious reflection not only on the trans-local coordinates that shape her own practice, but also on the museum as an institution exposed to external political and economic interests. This decisive situatedness provokes an ever-changing condition and turns away from the rigorous laws of the gallery setting. A sense of time creeps back into the space, exposing it to meteorology and scenes of the capital Taipei. We see traffic flowing continuously across the concrete beams of the Yuanshan Bridge, and a busy, large construction site frames the line of sight towards Taipei 101 through the eastern windows.

The view to the north is guarded by a transmission tower of Radio Taiwan International (RTI), Taiwan’s international public radio service. Gazing at the tower’s still-functioning structure up on the hill, we are in fact looking at a landmark of public diplomacy and Taiwan’s international communication activities. RTI was founded in 1928 as the Central Broadcasting System in Nanking (China) by the KMT’s Ministry of Defense. It was moved to Taiwan after World War II, appropriating the broadcasting stations built by the Japanese colonial government. From 1949 until 1998, it operated under the name “Voice of Free China”, broadcasting mostly in Mandarin Chinese and English. The service was renamed RTI in 1997 and currently produces content directed at foreign publics in several Chinese languages as well as in English, Japanese, Korean, Indonesian, Thai, Vietnamese, Spanish, German, French and Russian.[iv] RTI’s influential tactics have been a prominent theme in Ting-Jung Chen’s work and research since around 2018. Her long-term engagement with radio broadcasting as a political tool has focused on strategies of psychological and affective warfare in the “ideological war” between China and Taiwan during the Cold War, and in this context, on the Nationalist government’s radio broadcasts. Growing up in the 1980s in Taipei, Chen herself spent much of her childhood listening to the radio. In our conversation, she recalls listening to broadcasts as an everyday evening ritual before going to bed, referring to the radio as an intimate companion that could make unknown voices feel familiar.

The transmission station that we can see from TFAM’s window overlooks the Yuanshan area and also its most popular landmark, the iconic Taipei Grand Hotel. The hotel’s colossal architecture was designed to replace the National Martyr’s Shrine, a monument dedicated to the memories of the anti-Japanese war and a symbol of national loyalty. The aesthetic and style of the megastructure follow classical Chinese architecture.[v] Stories that haunt the Grand Hotel involve the political elite and its other guests, as the hotel served as a “national façade” for Taiwan during its period of martial law (1949-1987).[vi]

The RTI Broadcasting Center and the Grand Hotel in the back

Today, the fourteen-storey high-rise of the Grand Hotel remains a witness of the historic moments in Taiwan’s democratization process, including the negotiation meetings between the “ROC” and the US after their official diplomatic ties were cut in the 1970s. In 1986, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was founded here, as a new political party purposed to challenge Taiwan’s one-party system under the monopoly of the KMT(Kuomintang). It is without doubt that this panorama of the hotel, flanked by RTI’s transmission station and one of Taipei’s busiest freeways, provides quite a unique triptych of Taiwan’s modern political history. Exhibition visitors are invited to contemplate its architectural and spatial manifestations in relation to ongoing social, cultural and political urgencies.

Reporting radio reporting

Themes of geographic mapping and deconstruction continue to unfold through two video works, G03489 and A03598, at the opposite end of the gallery. The aerial shots displayed in the exhibition were taken by the U.S. Army for the purpose of topographic military mapping of Minxiong Broadcasting Station and its surrounding terrain in southern Taiwan, with the artwork titles corresponding to the serial numbers of their film canisters in Taiwan’s GIS (Geography Information System). G03489 displays historic footage of Minxiong Station, which served as a transmission station for the Japanese colonial government to broadcast to American troops in the Pacific during World War II. In a series of air raids, the US military in 1945 therefore tried to destroy the station and its infrastructure. The photos of G03489 vividly capture these attacks. A03598 instead shows the initial construction process of a new broadcasting station in 1959 in nearby Huwei, which was built with the purpose of broadcasting to the Chinese mainland.

Icon inflation

After passing a sculptural wall (Long Wave 3/4 of 2/3) 長浪3/4之2/3 that has been installed as a room partition, visitors meet a majestically inflated Chinese lion sculpture. Floating above ground in this small room at the back of the exhibition, the lonesome giant stares blankly towards Taipei 101. Conceptually related to the sound-based works, it epitomizes the concept of ideology-infused entertainment as a product of emblematic “Chineseness”.[vii]

Portraits of lions have appeared across cultures, depicting the animal as a noble and strong creature in the religious and national, among other contexts. While lions do not inhabit Taiwan, nor China, they have been popular as guardian figures and auspicious animals since imperial times. Although the guardian lion is now considered a spirit animal of genuine “Chinese” character, lions first came to China from the West via the Silk Road. The oldest records of lions as tribute gifts date back to Emperor Zhangdi in the Eastern Han Dynasty (87 CE). As only a privileged few were able to experience seeing the living animal, the majority of Chinese imported the lion's characteristics into fables, circulating the beneficial power of the mythical creature through their narratives.[viii] Flanking the sides of palace doors, imperial tombs, government offices, temples and private houses, their elitist aura is also associated with the fact that they were traditionally carved from stone, such as marble and granite, or cast in bronze or iron. Both the cost of the materials and the labor to reproduce them would only have been affordable for wealthy families. The lions are usually depicted in a highly stylized manner, with adornments such as collars and bells signaling their domestication, and attributes distinguishing their sex, such as an “embroidered ball” on which the male’s paw rests or a cub held by the claws of the female. The lion’s symbolic transposition into an Asian context has shaped distinct archetypes, involving patterns of synthetization and stereotyping, as well as forces of appropriation and fetishization.

For her graduation project at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Ting-Jung Chen commissioned a Taiwanese company specialized in PVC to fabricate the lion. Her 3D model reconstructed a bronze lioness that guards the front entrance of Taipei’s National Palace Museum. The animal’s domestic paraphernalia, a pinkish collar with bells and bow, were manually sewn by the artist in Vienna. Striking a shiny appearance in synthetic plastic, the resulting work transforms the Taipei bronze into an air-pressured form that is both iridescently powerful and vulnerable at the same time. Chen’s lion is best described in terms of an iconic-traditional-territorial-translocated-neoliberal assemblage. This assemblage brings together a signifier of power that is understood cross-culturally with a conflicted political reality, questions of access to guarded (and privatized) space, and the instrumentality of monumentalism, among other aspects. Both in its size and through its materiality, its figure also questions the cute-ified commerce that rules an instrumentalized contemporary materialism, especially in Taiwan. Exposing the iconic creature of the “Chinese lion” to its inherent hybridity, the work deals with how objects are invested with meaning, pointing to cultural meaning-making and its modern reconstruction as based on the fetish of commodity.

Lines of flight

In this exhibition, Ting-Jung Chen proceeds with subtle gestures of interlinking that press the aesthetic to its social context, the understanding of which is not a consequence, but the primal motivation of the work. As an assemblage-maker, Chen focuses on how collective memory and identity relate to patterns of both empowerment and control. She traces human agency and memory that entangle Taiwan’s search for “identity” through soundscapes and visual references.

During her art studies, first in Germany and later in Austria, Ting-Jung Chen used to introduce herself only as “Ting”, as it would be easier for the non-Chinese speakers she encountered to remember this short form of her Taiwanese name. This truncation of the artist’s name recalls a single light metallic sound, like that of a small bell. One could take it as the exhibition’s punchline: its complex sentence, formulated as a comprehensive gathering of several bodies of Ting-Jung Chen’s work, also includes several bell-based sounds.

While the concept of the white cube coopts the body, reducing one’s experience largely to the visual sense and the hermeneutics of cognition, this exhibition’s expanded spatial setting greatly affects the context in which the work and its audiences meet. Encompassing landmarks of TFAM’s geographic surroundings as relay-points for understanding the work, visitors are invited into an exercise of dialectical observation that draws attention to spaces of the in-between. Moving through this exhibition, we shift from an inverted to an exposed space, as if awakening from a buried dreamscape to a present-day reality, which then, inevitably, falls back into memory. Its spatial soundscape serves the purpose of connecting, overlapping and disturbing this experiential state. The bells’ presence especially recollects an infinite potential for interruption, a need to tirelessly break the continuum of historical time.

Notes

[i] Following Deleuze, an assemblage (from the French agencement) hardly amounts to a fully-fledged theory. While the term has already been much stressed in an art context and is applied in an undogmatic manner throughout this text, its operative methodology functions well for this particular exhibition. See Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London / New York City: Continuum 2008.

[ii] See Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” in Annual Review of Anthropology 42, 2013. 327–343, 327.

[iii] Editor’s note: Moonlight Serenade was adapted from Sayon’s Bell, a song written by Japanese composer Koga Masao in 1940.

[iv] See Colin Alexander, “Taiwan’s Public Diplomacy” in: Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Taiwan. Ed. by Gunter Schubert. New York: Routledge 2016. 547.

[v] Cho-cheng Yang, the hotel’s architect, was later commissioned to plan the sites of the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall and the National Theatre of Taipei, as well as the expansive public memorial square between them.

[vi] See Lu Pan, “Taipei’s National Martyrs’ Shrine: The Past and Present Lives of a Difficult Monument,” in: Frontiers of the Memory in the Asia-Pacific: Difficult Heritage and the Transnational Politics of Postcolonial Nationalism. Ed. by Shu-mei Huang, Hyun Kyung Lee, and Edward Vickers. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press 2022. 72.

[vii] I employ the notion of “Chineseness” as a critical label, inspired by Rey Chow who formulated it to function as a “distinguishing trait” in what otherwise would be “mobile, international practices.” The inherent problematic of this label is undoubtedly further complicated when applied to the context of present day Taiwan, and is used in this text only to highlight the very constructedness of the idea of a monolithic Chinese identity. See Rey Chow: “On Chineseness as a Theoretical Problem,” in: boundary 2, Vol. 25, No. 3, Modern Chinese Literary and Cultural Studies in the Age of Theory: Reimagining a Field, Autumn 1998. 1-24.

[viii] See Huping Shang: The Belt and Road Initiative: Key Concepts. Singapore/Peking: Peking Univ. Press and Springer Nature Singapore 2019. 72